"Hell is other people."

— Jean-Paul Sartre, *No Exit*

Society & Culture

When individual rationality creates collective absurdity. When everyday decisions lock everyone in place.

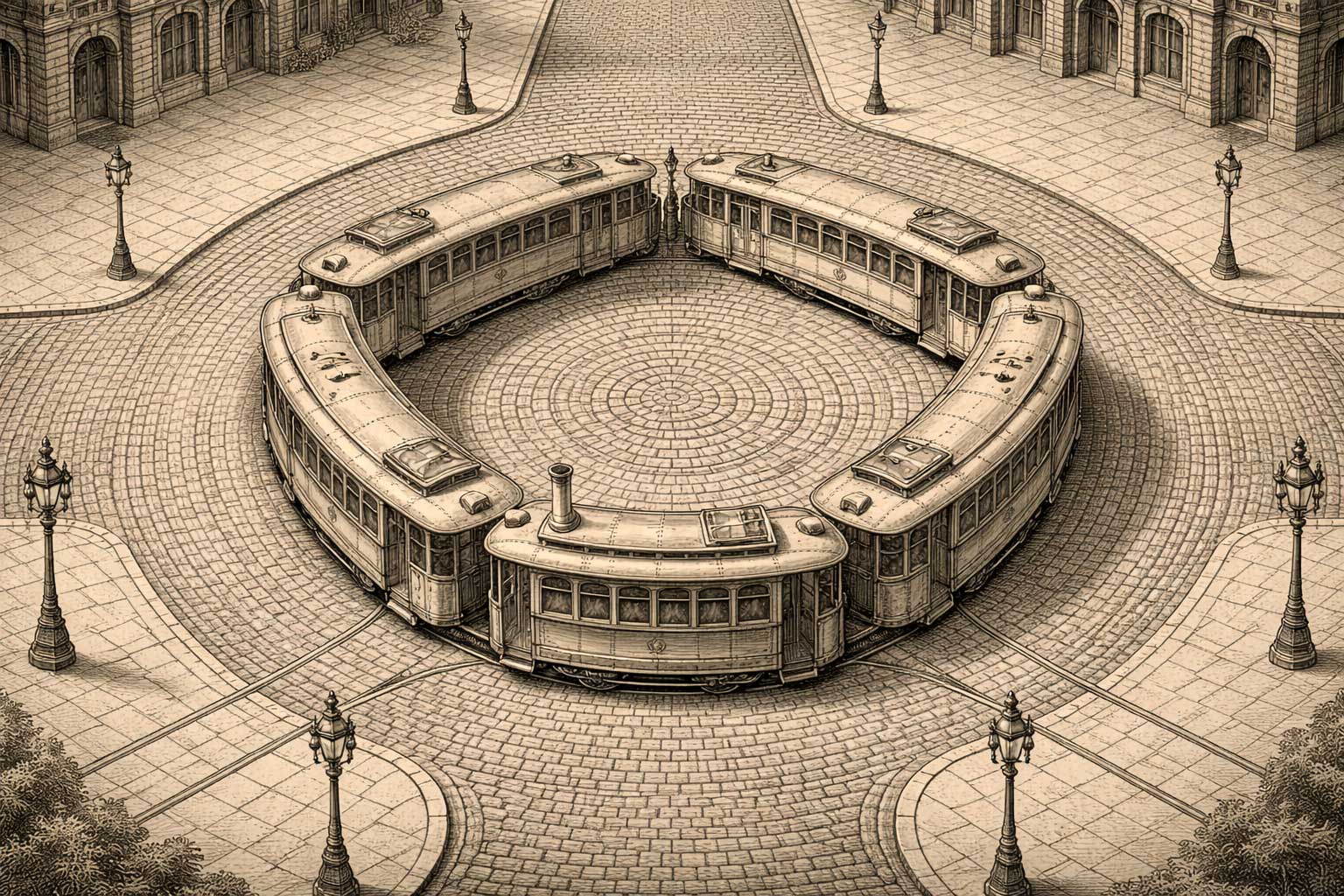

Oslo Roundabout Gridlock (November 2025)

The structure:

Four articulated buses approach a roundabout from different directions. Each driver sees space to enter. Each enters. In the center, they meet. No one can move forward—the next bus is in the way. No one can reverse—articulated buses don't reverse easily in tight spaces. Perfect gridlock.

Why each actor is rational:

- Driver A: Sees gap, enters (that's how roundabouts work)

- Driver B: Sees gap, enters (waiting would block traffic behind)

- Driver C: Sees gap, enters (no signal to wait)

- Driver D: Sees gap, enters (same logic)

Why it fails collectively:

Roundabouts assume sequential entry. Four simultaneous entries create structural impossibility. No coordination mechanism exists. No one did anything wrong. Everyone is stuck.

The trap: Four correct decisions produce zero movement.

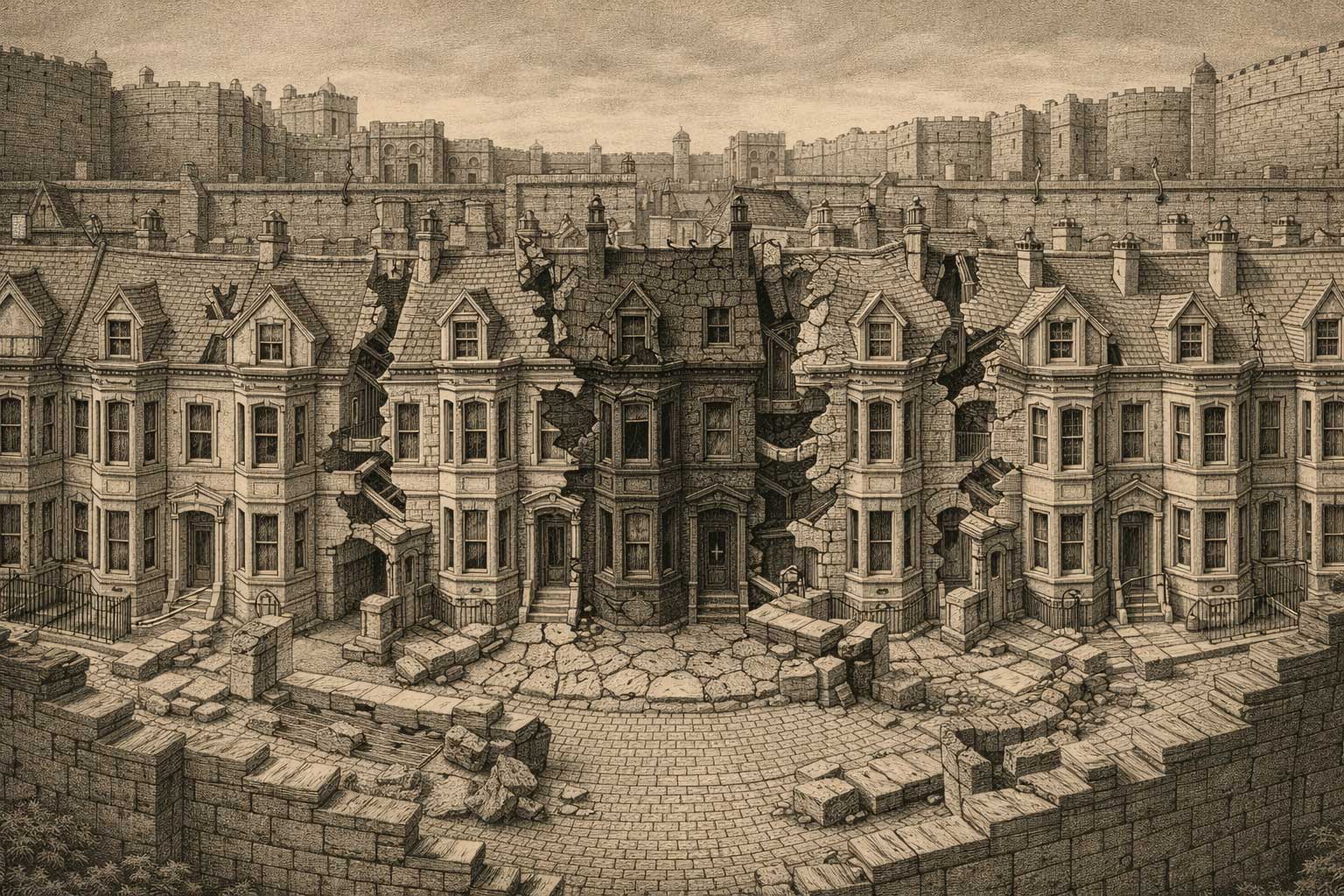

Black-Sheeping

The structure:

One member of a group commits a visible wrong. The outside world generalizes: "If one is like this, the whole group might be." White sheep cannot expel the black sheep (legally impossible, structurally unfeasible). The majority attacks the entire group, not just the perpetrator. Simultaneously, the herd disintegrates from within—suspicion spreads, proximity to the black sheep becomes guilt, white sheep isolate each other. Collective punishment from outside. Mutual suspicion from inside.

Why each actor is rational:

- The black sheep: Acts in self-interest, exploits group protection

- The outside majority: Uses heuristics (faster than individual assessment), seeks protection from perceived threat

- Media: Reports the sensational case (audience demands it)

- White sheep near the black sheep: Try to distance themselves, but movement confirms suspicion

- White sheep far from black sheep: Avoid "contamination," isolate potentially "tainted" members

- Legal system: Bound by due process, cannot act instantly enough to prevent mob reaction

Why it fails collectively:

Innocents punished for another's crime. The group fractures through mutual distrust—those near the black sheep become suspect, proximity becomes evidence. Mob justice targets the wrong people. Internal paranoia destroys group cohesion. The actual perpetrator often escapes while others suffer. Spiral of violence and exclusion begins. The herd eliminates itself.

The trap: One bad actor defines the whole group. Collective punishment becomes "self-defense." Internal suspicion becomes "necessary caution."

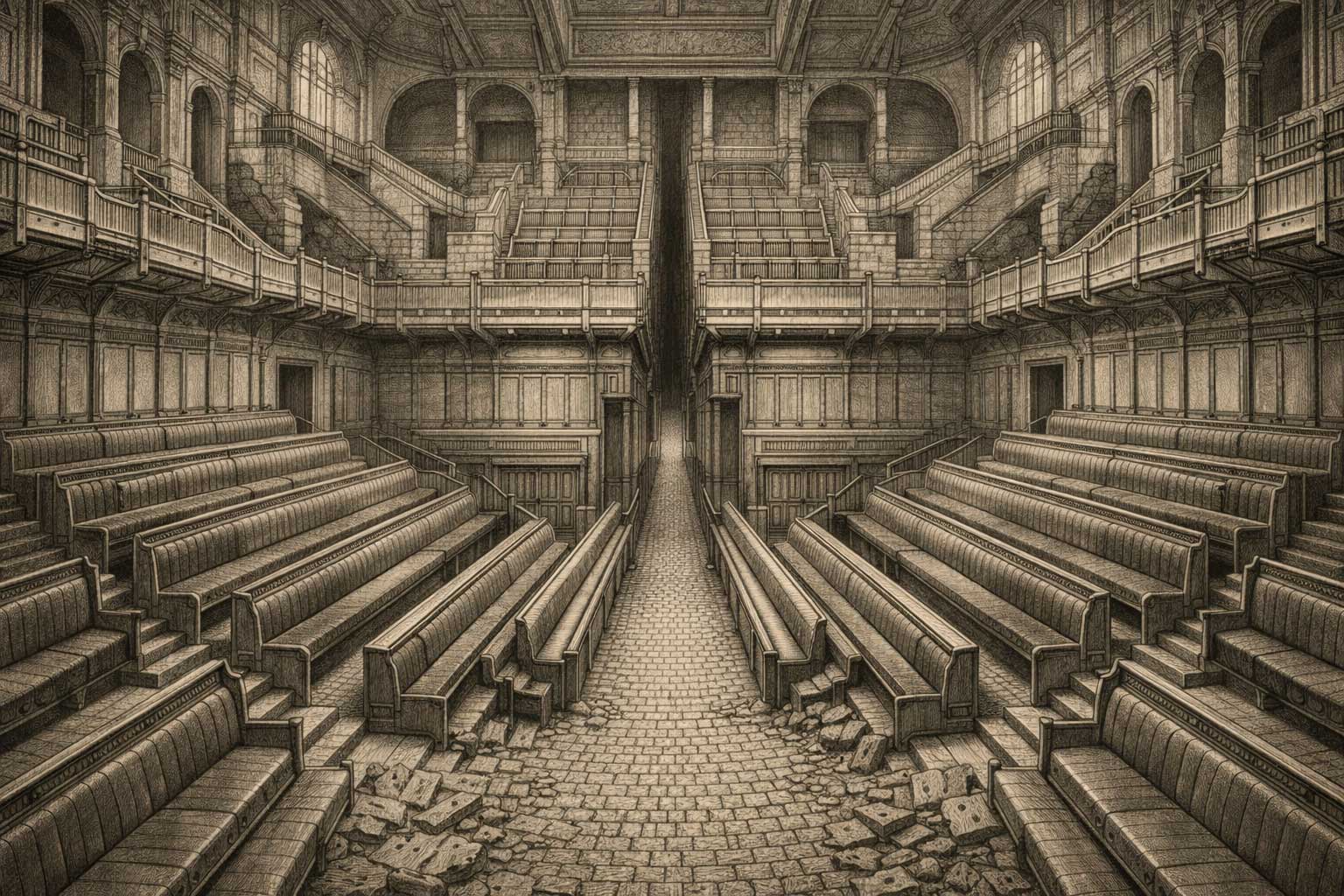

The Median Trap

The structure:

Democracy requires living debate—innovation, risk, dissent. Majorities form around consensus—the familiar, the safe, the moderate. Elections reward consensus. Innovation gets punished ("too extreme," "unelectable," "dangerous"). Result: The system cannibalizes its own vitality. The moderates hollow out what they claim to protect.

Why each actor is rational:

- Politicians: Move to the center (Median Voter Theorem—that's how you win)

- Voters: Choose safe bets (risk aversion, recognition over quality)

- Media: Cover the electable (that's where the story is)

- Parties: Nominate centrists (extremes lose elections)

- Institutions: Protect stability (that's their function)

Why it fails collectively:

Democracy optimizes for electability, not excellence. The median voter determines outcomes. Brilliance and idiocy are equally excluded—both "too extreme." Consensus becomes the goal. Innovation dies. The system protects itself by eliminating vitality. Everyone quotes Goethe. No one writes like Goethe anymore—too risky, too uncertain. Literature becomes canon management. Dead, but "civilized." The quoters are the killers. They don't notice.

The trap: Democracy prevents tyranny by preventing excellence. The moderates are the cannibals. They consume what they protect. Civilization becomes museum administration.

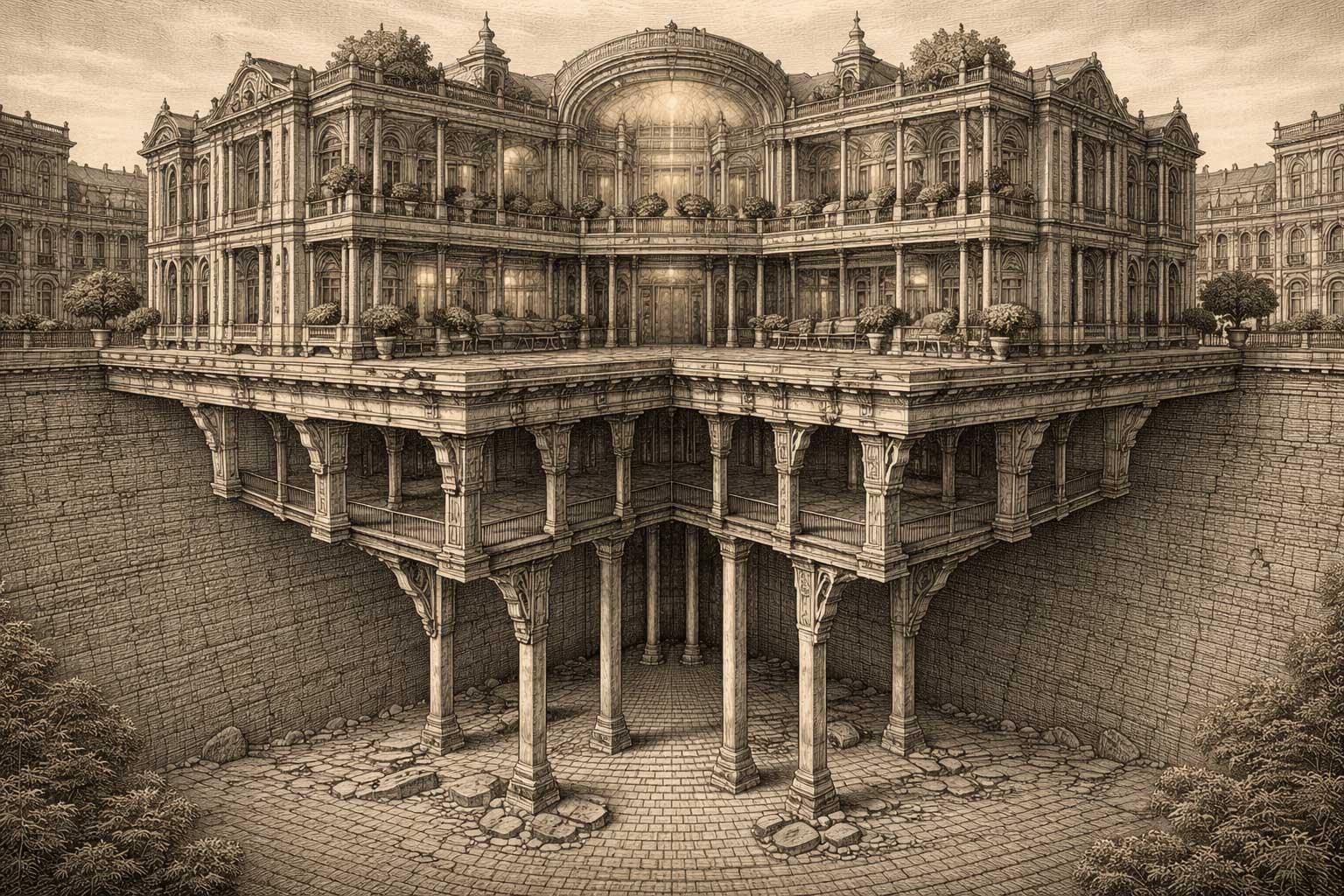

The Solidarity Trap

The structure:

Solidarity systems promise: We carry risks together that no one could bear alone. Works brilliantly—until success shifts the math. Healthcare keeps people alive longer (wonderful). Those people need expensive treatments longer (the pot shrinks). More elderly, fewer young contributors. The young calculate: I pay more for less. Solidarity crumbles precisely where the system proves it works.

Pension systems: generational contract assumes demographic stability. System works (good pensions, long lives), birthrate drops. Why? Well-secured people don't need children as retirement insurance. Next generation smaller, carries more burden, has even fewer children. The pyramid inverts. The system dies from its success.

Marriages: The security they provide breeds complacency. No need to fight, court, prove oneself anymore. This relaxation erodes what stabilized the bond. Or reverse: the better the system works (reliable partnership), the more attractive options outside become (because you're secure, you can take risks). The net that holds invites the jump.

Why each actor is rational:

- Today's contributors: See predecessors got more than they paid in, expect less themselves (math is correct)

- Beneficiaries (elderly, sick, secure partner): Paid in, honored the deal (legitimate claim)

- Young generation: Chooses fewer children (financial security works, reduces reproductive pressure)

- System designers: Maximize coverage and stability (that's the mission)

- Politicians: Protect beneficiaries (voters, legitimacy depends on it)

- Secure partner: Takes security for granted or explores options (human nature)

Why it fails collectively:

Every adjustment (raise retirement age, increase contributions, couples therapy) treats symptoms, not structure. The structure is: success destabilizes itself. Good pensions reduce birthrates. Lower birthrates break pension math. Healthcare success increases healthcare costs. Marital security enables exploration. The implicit deal—I pay in, I get out what I need—breaks when today's contributors see: those before us got more, we get less. The deal feels unfair even when mathematically correct.

All are guilty (the system fails). None are at fault (everyone followed the rules).

The trap:

Solidarity systems can't be "fixed" by making them fairer. Success breeds its own collapse. What remains: honesty about the structure. Pension systems won't hold—regardless of adjustments. Healthcare won't stay affordable. Marriages fail precisely because they worked. Stating this isn't defeatist. It's precise. And it enables navigation: build parallel structures while the old ones decay. Not as replacement (doesn't exist). As parallel reality.

The Prosperity Fairy Tale

The structure:

Promise: Economic growth creates prosperity for all. Reality: Growth requires inequality—capital accumulation, competition, winners and losers. Everyone acts rationally—companies maximize profit, workers sell labor, investors seek returns. The promise stabilizes the system: "Work hard, you'll benefit too." Result: Concentration at the top, precarity at the bottom. The fairy tale keeps the losers playing.

Why each actor is rational:

- Companies: Maximize shareholder value (that's their function)

- Investors: Seek highest returns (rational allocation)

- Workers: Sell labor, believe in upward mobility (no alternative)

- Politicians: Promise growth (legitimacy depends on it)

- Economists: Model growth scenarios (that's the discipline)

- Media: Celebrate success stories (American Dream narrative)

Why it fails collectively:

The promise is structurally impossible to deliver universally. Growth depends on unequal distribution—capital must accumulate somewhere. But the promise must be told, or legitimacy collapses. Winners need losers to believe they could win. The system requires the fairy tale. The fairy tale requires the losers.

The trap: The promise keeps the losers playing. Those who see through it become cynical. Those who believe stay trapped. Prosperity for all—as long as "all" means "the few."

The Attention Paradox: Interesting vs. Engaging

The structure: Limited attention. "Interesting" defined by engagement metrics. Spectacular content generates immediate clicks. Substantive content requires effort, yields delayed understanding. Algorithms reward instant engagement. Deep work gets buried under viral noise. Everyone complains about shallow discourse while clicking on the next outrage. Why each actor is rational:

- Content creators: - Make spectacular—it gets reach (survival)

- Audience: - Choose easy over hard—time is scarce (efficiency)

- Platforms: - Optimize for engagement (that's the metric)

- Advertisers: - Pay for eyeballs, not depth (ROI logic)

- Quality creators: - Produce depth, get ignored (mission unchanged)

- Media: - Cover what's viral, not what matters (audience demands it)

Why it fails collectively: The truly interesting (complex, nuanced, requiring thought) loses to the immediately engaging (simple, emotional, requiring no effort). Public discourse flattens. Knowledge that demands work dies. Collective intelligence degrades while individual choices remain rational. The trap: Depth doesn't scale. Spectacle does. The interesting loses to the engaging. Always.

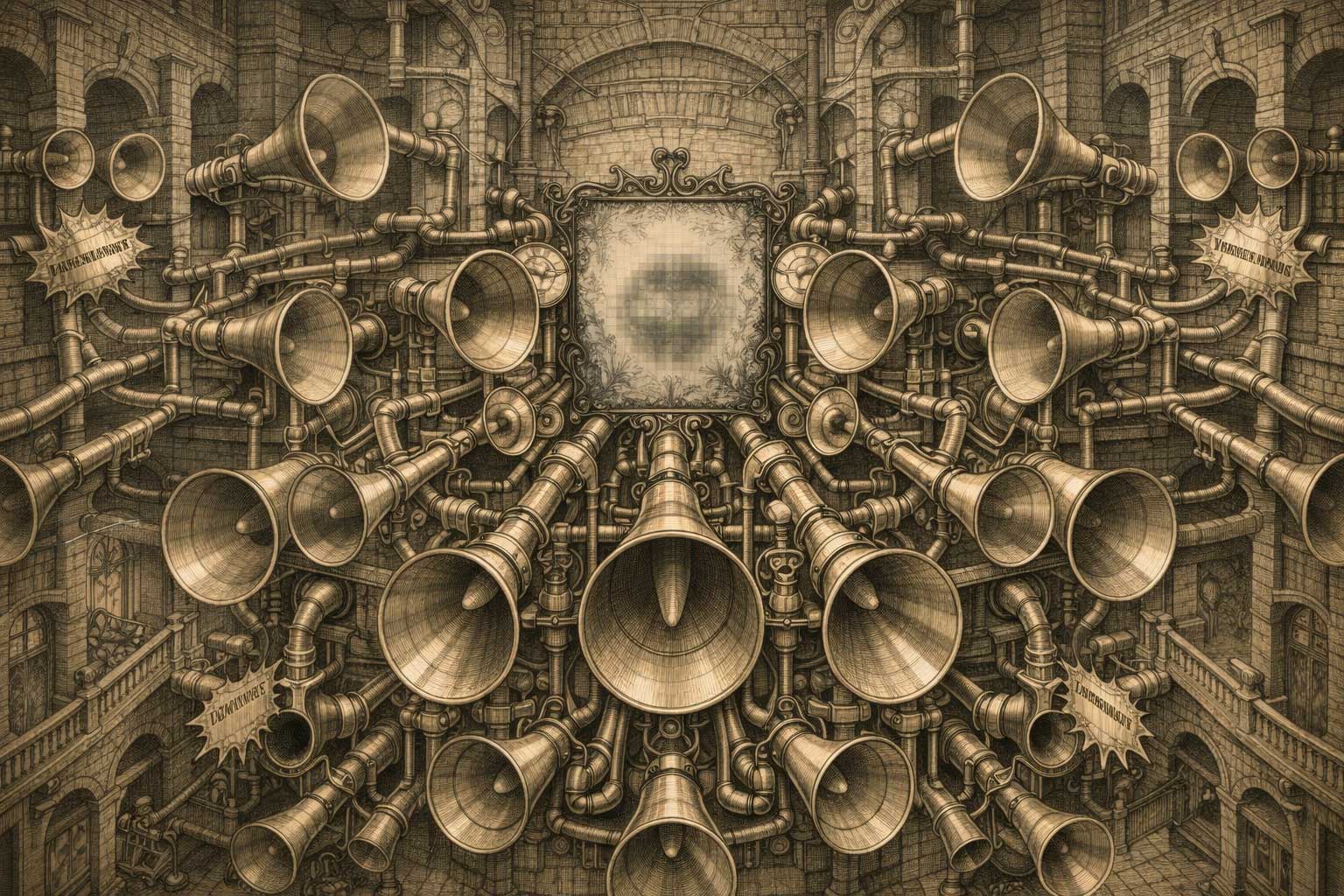

Viral Outrage Cycles

The structure:

Someone posts something offensive. People share it to express outrage. Algorithm sees engagement, amplifies the post. More people see it. More outrage. Original poster gets attention (punishment or reward, depending on intent). Those who shared to condemn it gave it reach. The condemnation becomes the distribution mechanism.

Why each actor is rational:

- Original poster: Posts for attention/provocation (works)

- Outraged users: Share to condemn (moral duty)

- Platform: Amplifies engagement (that's the algorithm)

- Advertisers: Pay for eyeballs (outrage delivers)

- Media: Report on viral content (that's news)

Why it fails collectively:

Condemnation spreads the thing being condemned. Silence would starve it of oxygen—but silence feels like complicity. Engagement punishes the behavior while rewarding the actor. The megaphone is the response.

The trap: Fighting it feeds it.

The Prophet's Trap: Self-Fulfilling Prophecy

The structure:

Someone with credibility warns of danger. People hear the warning. The warning

changes their behavior. The changed behavior creates the predicted outcome.

The prophet becomes the first victim of what they predicted—not despite their

warning, but because of it.

Why each actor is rational:

- The Prophet: Sees genuine risk, warns to prevent it (moral duty, rational analysis)

- The Audience: Acts on the warning (rational risk avoidance)

- Media: Amplifies the message (newsworthy, public interest)

- Institutions: Prepare for predicted scenario (prudent planning)

Why it fails collectively:

The warning meant to prevent becomes the trigger that creates. Bank run

classic: economist warns bank is shaky → depositors panic → bank collapses.

Political prediction: "This policy will fail" → stakeholders withdraw support

→ policy fails. Market forecast: "Prices will drop" → investors sell → prices

drop. The prophecy carries its own fulfillment mechanism.

The trap: Speaking the truth creates the catastrophe. Silence

might have prevented it. The prophet is "guilty" of triggering the outcome,

but not "at fault"—they acted rationally to prevent it.

Cassandra's Trap: The Prophet Without Credibility

The structure:

Someone sees genuine danger and warns. No one believes them. The warning is

dismissed, mocked, or ignored. No preventive action is taken. The predicted

catastrophe occurs. The prophet is vindicated posthumously—when it's too late.

Why each actor is rational:

- The Prophet (Cassandra): Sees real risk, sounds alarm (moral duty, accurate analysis)

- The Audience: Dismisses warning (prophet lacks credentials, timing seems wrong, claim sounds extreme)

- Gatekeepers: Block access to platforms (protect credibility standards, avoid false alarms)

- Media: Ignore the story (no established source, not newsworthy yet)

- Experts: Defend consensus (outsider critique threatens professional standing)

- Institutions: Maintain course (changing based on unverified warnings is costly)

Why it fails collectively:

Credibility filters exist for good reason—they prevent panic from false

alarms. But they also filter out accurate warnings from non-credentialed

sources. The system optimizes for stability, not truth. When the catastrophe

hits, everyone asks: "Why didn't anyone warn us?" They did. You didn't listen.

Worse: the ridicule of early warners discourages future warnings. The next

Cassandra learns to stay silent.

The trap: The prophet with credibility triggers the

catastrophe (self-fulfilling prophecy). The prophet without credibility is

powerless to prevent it (ignored warning). Both are "guilty" of the

outcome—one through triggering reaction, one through failing to trigger it.

Neither is "at fault"—both acted rationally. The double bind: as prophet, you

lose either way.

Tragedy of the Commons (Modern Edition)

The structure:

Shared resource (atmosphere, ocean, public space, attention economy). Each actor takes slightly more than sustainable. Individually rational—the cost is distributed, the benefit is personal. Collectively catastrophic—the resource degrades. Everyone knows this. No one can stop first (would only lose without saving the resource).

Why each actor is rational:

- Individual actors: Maximize personal benefit (survival logic)

- Competitors: If I don't take it, someone else will (true)

- Regulators: Lack enforcement power across jurisdictions

- Beneficiaries: Enjoy lower costs from exploitation

Why it fails collectively:

Individual restraint is irrational (you lose, nothing changes). Collective restraint requires coordination no one can guarantee. The resource dies while everyone watches, knowing exactly what's happening.

The trap: Knowing doesn't help. Caring doesn't help. Acting alone doesn't help.

More examples in this category coming soon.